Art and Fascism

- When: April 14, 2024 - September 01, 2024

- Place: Rovereto, Mart

- Region: Trentino Alto Adige

Modern artArt Exhibitions in Trento

From April 14th to September 1st, 2024, the Mart in Rovereto presents the exhibition "Art and Fascism," conceived by Vittorio Sgarbi and curated by Beatrice Avanzi and Daniela Ferrari. The exhibition examines the various and complex ways in which the fascist regime influenced Italian figurative production, using the languages of art and architecture for propagandistic purposes.

The "Art and Fascism" exhibition examines the various and complex ways in which the fascist regime influenced Italian figurative production, using the languages of art and architecture for propagandistic purposes.

The return to antiquity, functional for the affirmation of Italian tradition, finds various declinations, from the renewed gaze at the ancient masters by the protagonists of the Novecento to more radical affirmations of propaganda art aimed at building consensus. The same model of a rediscovered harmony between tradition and modernity enjoys support from the regime, in search of defining an organized "system of the arts."

At the same time, the new centers of power become tools of affirmation through a language open to both classicism and rationalism, involving architecture, sculpture, and mural art, reborn under the impetus of a renewed celebratory will.

The exhibition recalls the main occasions when artists gave voice to the ideology, themes, and myths of fascism through participation in Biennales, Quadrennials, trade shows, competitions, and public commissions.

Among painting, sculpture, documents, and projects, the exhibition path winds through approximately 400 works by artists and architects such as Mario Sironi, Carlo Carrà, Adolfo Wildt, Arturo Martini, Marino Marini, Massimo Campigli, Achille Funi, Fortunato Depero, Tullio Crali, Thayaht, Renato Bertelli, Renato Guttuso. Coming from public and private collections, the works engage in dialogue with some of the great masterpieces of the Mart and with numerous materials from the Archives of the '900.... read the rest of the article»

Rooted in the decades preceding and ranging from traditional practices to applied arts, the visual culture of the Ventennio witnesses the development of a variety of unprecedented styles. Unlike other regimes, the fascist one does not impose a taste, but it also adopts some of the artistic trends that emerge in that historical period. The lack of a single orientation facilitates the development of a heterogeneous and dynamic presence of expressions and currents. Alongside the persistence of avant-garde research linked to Futurism, a line of "return to order" emerges, converging into the movement of Italian Novecento, created by Margherita Sarfatti. The return to antiquity, functional for the affirmation of Italian tradition, finds various declinations, from the renewed gaze at the ancient masters by the protagonists of Novecento to more radical affirmations of propaganda art aimed at building consensus.

The model of a rediscovered harmony between tradition and modernity enjoys consensus from the regime, in search of defining an organized system of the arts. An extraordinary apparatus of awards, public exhibitions, conventions, and shows allows the regime to intercept the most significant artists, support their work, and incorporate them into the broader project of general promotion. Through participation in biennials, quadrennials, trade shows, competitions, and public commissions, artists give voice to the ideology, themes, and myths of fascism.

The relationship between artists and power itself is neither defined nor unique. Alongside openly fascist figures, convinced supporters of the Duce like Depero and Sironi, there are artists less engaged, more or less distant but still present in the rich Italian panorama.

At the same time, the new centers of power become tools of affirmation through a language open to both classicism and rationalism, involving architecture, sculpture, and mural art, reborn under the impetus of a renewed celebratory will.

Among painting, sculpture, documents, and archival materials, the exhibition path winds through 400 works by artists and architects such as Mario Sironi, Carlo Carrà, Adolfo Wildt, Arturo Martini, Marino Marini, Massimo Campigli, Achille Funi, Fortunato Depero, Tullio Crali, Thayaht, Renato Bertelli, Renato Guttuso. Coming from public and private collections, the works engage in dialogue with some of the great masterpieces of the Mart and with numerous materials from the Archives of the '900.

Eight chronological and thematic sections mark the visit: Italian Novecento, dedicated to Margherita Sarfatti's major support project for artists and culture, an intellectual and curator avant la lettre; The image of power, on the iconography of the Duce between the celebration of the leader and the spread of the myth; Futurism. Celebrating action, the total art of the major Italian avant-garde; The social function of public art, education and propaganda through large mural art, mosaics, frescoes, decorations, monuments; Architecture and the relationship with the arts, projects, sketches, and abstract art for grandiose buildings that exalted Italian power, New myths, not only the hero and the athlete but also the worker, the woman, the family, in search of the definition of a virtuous social system; The system of the arts, the organization of state art between exhibitions, quadrennials, biennials, and competitions; The fall of the dictatorship, the end of an era between iconoclasm, satire, and drama.

The setup is designed by Baldessari and Baldessari.

The catalog

The exhibition is accompanied by a rich catalog published by L'Erma di Bretschneider with essays by some of the leading scholars of the period, an introduction by Vittorio Sgarbi, the texts of the exhibition curators and researchers from the Mart's Archive of the '900.

Exhibition path

In what ways did the fascist regime influence figurative culture during the Ventennio? How did the complex art system develop, and how did artists give voice to the ideology, themes, and myths of fascism?

The Mart exhibition seeks to answer these questions by narrating, through eight thematic sections, the coexistence of different artistic languages during the dictatorship. Unlike other regimes, in fact, fascism does not impose a style but adopts some of the trends that emerge during that period.

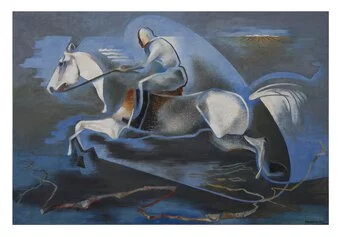

The path starts with Italian Novecento, the movement promoted by Margherita Sarfatti that debuted with Mussolini's rise to power. The image of the dictator is the protagonist of the second section, where avant-garde and classic visions that interpret the celebratory theme of the Duce's portrait are compared. If the return to antiquity of Novecento appears in line with the affirmation of the greatness of Italian tradition, Futurism shares with fascism the interventionist and revolutionary thrust. A particularly important theme is represented by the impetus given to architecture and mural decoration and how painters and sculptors measure themselves with the social function of public art. Themes conveying fascist ideals emerge, such as that of the family, sports, and work. By the late 1930s, propaganda art aimed at consensus-building begins to prevail, and an organization that disciplines art policy through unions, corporations, commissions, awards, and competitions is consolidated. The outbreak of war marks the end of this self-celebratory parabola, as can be seen in the last section, dedicated to the fall of the dictatorship.

Italian art in the early twentieth century

In the early twenties, Margherita Sarfatti played a leading role in guiding Mussolini's taste and attention towards the visual arts. As Prime Minister, he intervened at the inauguration of the first exhibition of the Seven Artists of the Twentieth Century, held in 1923 at the Galleria Pesaro in Milan, stating that he did not want to encourage a state art, because "Art belongs to the individual sphere. The State has only one duty: not to sabotage it [...]".

The painters who formed the original group - Bucci, Dudreville, Funi, Malerba, Marussig, Oppi, and Sironi - are all represented in this section, accompanied by other artists who participated in exhibitions organized by Sarfatti starting in 1926, when the movement officially took the name of Italian Twentieth Century.

Each of them paints differently, from the archaic stylizations of Campigli to the suspended atmospheres of Casorati, from the concentration on tonal values of Morandi to the heavy and square masses of Sironi's figures, but for all of them Sarfatti's words apply: "clarity in form and composure in conception," as well as those of Lino Pesaro who emphasizes the desire to "make pure Italian art, drawing inspiration from its purest sources, removing it from all imported 'isms'."

The image of power

The fascist twenty-year period sees a widespread dissemination of the image of Benito Mussolini. His effigy is used for propaganda purposes and consensus building, through the exaltation of physiognomic and character traits that become metaphors for power.

The evolution of Mussolini's iconography follows the course of events, reflecting the Duce's rise to a dictatorial regime and his imperial ambitions. The portraits of the twenties represent the prime minister in bourgeois attire, in the wake of the portrait of nineteenth-century matrix, although ideal portraits are not lacking that make him the personification of a renewed classicism, such as the monumental bust commissioned to Wildt by Sarfatti for the Casa del Fascio in Milan. Here the dictator appears, severe and hieratic, dressed as a Roman emperor. This classicist iconography will be even more affirmed in the thirties, to legitimize Italy's colonial expansion.

During this period, the image of the Duce prevails as an emblem of strength and progress, modernized by the style of futurist artists who portray him as a "brand new" hero: a leader on horseback, a helmsman at the helm of the nation, an aviator. In the sculptures of Thayaht and Bertelli, Mussolini's head transforms into a metallic helmet or into a dynamic synthesis that expresses strength and energy, a profile that rotates 360 degrees, a metaphor for someone who sees and controls everything. As Carlo Belli writes: "a moving candor urged us to believe that fascism was the instigator of a lucid European modernity!".

Futurism. Celebrating action

Mussolini's relationships with Marinetti and the futurist movement are complex and not always straightforward, between separations and returns, admiration and detachment. Fascism and Futurism share the myth of action, interventionism, the aesthetics of war and mechanical means, especially airplanes, the charm of science and technology. In the thirties, the aeropainters and artists of the second season of the movement embrace the regime's propaganda needs, celebrating its ideals and even coining the term "futur-fascism." However, the avant-garde fails to carve out a leading role in the cultural policy of the twenty years, as can be understood from the modest quantity of futurist works that entered public collections and the limited involvement of artists such as Prampolini, Balla, and Depero in major state commissions.

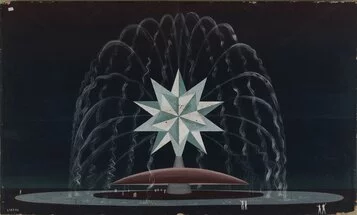

While Futurism never becomes state art, the movement is crucial in establishing something more important: a modern aesthetic in Italy. An innovative visual language that exploits all the opportunities offered by the vast self-celebratory system of the regime, expressing itself in graphics and illustration, in pavilion layouts and exhibitions, in images reproduced in series, amplifying to the highest degree this new aesthetic.

The social function of public art

The Manifesto of mural painting, signed by Sironi, Funi, Campigli, and Carrà in 1933, emphasizes the collective and moral value of large-scale decoration, its social destination, and its ability to express ideal values. Public art, unlike that intended for bourgeois salons, must be accessible to all, and Sironi hopes for a rebirth of the arts resulting from the complementarity of art and architecture. "When we talk about mural painting," the artist writes, "we do not mean only the pure enlargement on large surfaces of paintings that we are used to seeing [...]. Instead, new problems of spatiality, form, expression, lyrical or epic or dramatic content are envisaged".

The question of technical skill and knowledge of the craft proves to be fundamental in facing the difficulties of large-scale mosaic or fresco decoration. In addition to Sironi, engaged in the decoration of the Aula Magna of the University La Sapienza in Rome, Achille Funi measures himself with this technique, for which Minister Bottai establishes the first fresco chair in Italy, at the Brera Academy. The preparatory cartoons exhibited in the exhibition highlight his preference for mythological subjects or those drawn from ancient history, in tune with Novecento classicism.

Among the sculptors particularly active in the field of public art is Arturo Martini who, in the new Palace of Justice in Milan, places the grandiose marble bas-relief Corporate Justice, here in a smaller bronze fusion.

Architecture and the relationship with the arts

In 1933 Antonio Maraini, head artist of the National Fascist Union of Fine Arts, writes about the "wonderful sprouting of palaces, squares, streets open to life, study, and the traffic of the nation" on which fascist art was being founded.

Architecture is considered the most important of the arts for its role in representing power and in building a modern nation. It is indeed at the center of the regime's exhibitions, promoted by events such as the Milan Triennale and spread by magazines.

The imposing plan of construction desired by fascism gives impetus to the economy by investing both in the renovation of historic cities and in the foundation of new villages and urban centers such as Littoria, Sabaudia, and other locations in the Agro Pontino, recently reclaimed. In particular, public works are carried out that play a fundamental role in bringing fascist ideology into the private lives of citizens: schools, stations, courthouses and post offices, fascist houses, sports complexes like the Foro Mussolini. With these themes, the architects of the time measure themselves, interpreting the international language of Rationalism or reconciling the essential forms of modern architecture with a monumentality that the regime imposes with increasing insistence after the mid-thirties, when it wants to emphasize the link with imperial Rome. This celebratory grandeur reaches its peak in the projects for the Universal Exhibition of 1942, for which a new district south of Rome is destined.

From the '900 Archive of the Mart comes the majority of the exhibited projects, which concern figures such as Angiolo Mazzoni, an official of the Ministry of Communications, Adalberto Libera, Luigi Figini and Gino Pollini, Giuseppe Terragni.

New myths

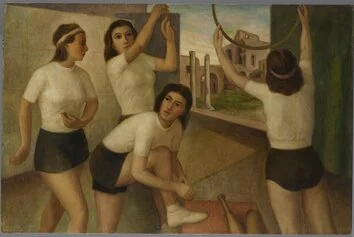

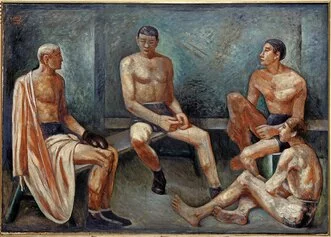

Fascist ideology suggests new themes to artists that contribute to the narrative of a country of heroes, athletes, and peasants. In particular, the well-built and trained body, geared towards movement and competition, represents the noblest expression of a people's vitality. The cult of the body has its roots in classical tradition, and some modern sports disciplines originate from physical activities practiced in ancient Rome. During the fascist regime, sport is considered one of the values of Italian society, and we can see the reflection of this belief in the proliferation of artworks featuring swimmers, footballers, wrestlers, runners, or boxers.

The classical exaltation of the human figure is also present in other subjects dear to the regime, such as work and family. Consistent with the goal of demographic increase, the family plays a central role in fascist society, which imposes a traditional and anti-bourgeois vision that favors large families tied to the land.

For example, Carlo Bonacina dedicates some of his paintings and frescoes to The Rural Family, edifyingly representing the peasant environment in which he lived from 1931, after his transfer to a valley in Trentino.

That portrayed by the sculptor Arrigo Minerbi, instead, is the family of origins, with the ancestors gathered around the fire and surrounded by a nature with which they are still perfectly in harmony.

The arts system

Unlike other dictatorships, fascism does not impose a true "state art" but prefers to control and direct artistic production through a widespread system of awards, subsidies, and exhibitions. This complex system of the arts guarantees a certain plurality of languages and, at least until 1938, allows most artists to benefit from the regime's support for the development of the arts. After the promulgation of the racial laws, however, painters, sculptors, and architects of Jewish origin are denied the right to design, teach, exhibit, and sell their works.

During the twenty years, new exhibitions are born: the Milan Triennale and the Rome Quadrennial accompany the Venice Biennale, while at the end of the thirties, two competitions are established: the Bergamo Prize and the Cremona Prize. Born at the initiative of Minister Bottai, the Bergamo Prize sees the participation of artists with a strong expressive originality such as Guttuso, Birolli, Morlotti, Capogrossi, Rosai. The Prize desired by the hierarch Farinacci in Cremona, instead, aims to be a clear expression of fascist art. With it, the interference of politics in art is manifested, and the desire to forge an alliance with Nazi Germany, which in 1941 will host the exhibition of its third edition in Hanover. The works of Cesare Maggi and Alfredo Catarsini are an example of how artists interpret, with a simple and understandable language, the propaganda subjects dictated by the regime: "Listening to the Duce's speech on the radio" and "The battle of wheat."

The fall of the dictatorship

Between the late thirties and the early forties, the first signs of the dictatorship's crisis are evident. After years of celebration, it is time for some artists to express harsh and relentless criticism, hitherto prohibited.

For many of them, who had militated in the ranks of fascism, it is a drastic change of course. This is the case of the "wild fascist" Mino Maccari, who, in the summer of 1943, presents at his home in Cinquale the series Dux: paintings and drawings created "with joyous and at the same time tragic fury." Always an irreverent observer of society's malaise, caricature illustrator, and then director of the magazine "Il Selvaggio," he gives life to merciless parodies of a grotesque and dissolute Duce.

In this period, Mario Mafai, fleeing with his family to escape the racial laws, creates his Fantasie, a pictorial cycle of hallucinated violence denouncing the brutality of war, as Goya did in the past with his Caprichos. But the most irreverent and mocking satire is that of the Hunchback drawn by Tono Zancanaro, a caricature of a violent and obscene Duce who embodies the vices and evils of the entire society.

Inexorably, with the end of the regime, its symbols fall: the effigies of the dictator that had been objects of worship are struck by the iconoclastic fury that accompanies the decline of every tyranny. We are reminded of this by the bronze bust Dux by Adolfo Wildt, damaged by the partisans in the days of Liberation.

Title: Art and Fascism

Opening: April 14, 2024

Ending: September 01, 2024

Organization: Mart

Curator: Beatrice Avanzi e Daniela Ferrari

Place: Rovereto, Mart

Address: Corso Bettini 4 - 38068 Rovereto (TN)

Opening hours: Tuesday-Sunday 10:00-18:00 | Friday 10:00-21:00 | Closed on Monday

Ticket: Full price €15 | Reduced price €10 (single ticket for all Mart locations) | Free for children up to 14 years old and people with disabilities

For information: +39 0464 438887 | info@mart.tn.it | Toll-free number 800.397760

Catalog: published by L'Erma di Bretschneider

More info on this website: https://www.mart.tn.it/

Other exhibitions in Trento and province

Contemporary artexhibitions Trento

Andrea Fontanari. The monumental ordinary

Boccanera Gallery presents The monumental ordinary, the new solo exhibition of the Trentino artist Andrea Fontanari (Trento, 1996). read more»

itinerarinellarte.it è un sito che parla di arte in Italia coinvolgendo utenti, musei, gallerie, artisti e luoghi d'arte.

itinerarinellarte.it è un sito che parla di arte in Italia coinvolgendo utenti, musei, gallerie, artisti e luoghi d'arte.